1. Foundations of Privacy and Data Protection#

1.1. Introduction#

Privacy has become one of the central concerns of the digital age. As societies rely increasingly on data-driven systems, the ways in which personal data is collected, processed, shared and protected deeply affect both individuals and institutions. While this chapter focuses on privacy, it is closely related to the broader field of information security and to the regulatory frameworks that govern how data may be used.

In this chapter, we introduce the key conceptual, ethical, legal and technical foundations of privacy and data protection, with particular emphasis on the European context and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Although many examples refer to health and biomedical data, the ideas discussed here apply broadly to any domain where personal information is handled.

1.2. Security and Privacy#

Privacy is often conflated with security, but they are not the same. Security focuses on protecting systems and data against unauthorized access, modification or destruction. Privacy focuses on the rights and interests of individuals whose data is being processed. The two areas overlap, particularly around confidentiality, but each has its own goals and tools.

Information security is often summarized by the so-called CIA triad: confidentiality, integrity and availability. Confidentiality is about ensuring that only authorized individuals or systems can read particular data. It is usually implemented through authentication, access control, encryption and other technical safeguards. Integrity is about ensuring that only authorized parties can modify data; any unauthorized change, even if unintentional, is treated as a violation of integrity. Availability refers to keeping systems and data accessible to authorized users when needed, including in the face of hardware failures, accidents or natural disasters. Together, these three dimensions define what it means for a system to be secure.

Privacy, in contrast, is usually described as control over personal data. It is very much related to confidentiality, since restricting access is one way of protecting privacy, but it goes further. Privacy raises questions such as: Which data about a person are collected? For what purposes? Who can use these data and for how long? What rights does the individual have to access, correct or delete the data? As soon as we ask these questions, we move from purely technical concerns to ethical and legal ones.

1.3. Ethical Foundations of Privacy#

The ethical foundations of privacy are especially visible in fields like medicine and biomedical research, but they apply broadly across society. A key principle is the idea of do no harm. Any activity involving personal data may have both potential benefits and potential harms. For instance, aggregating health records can improve medical research and care, but leaks of the same data may cause stigma, discrimination or emotional distress. Ethical practice requires us to weigh these risks and to take serious measures to prevent harm.

Privacy also relates closely to safety. Oversharing information about daily routines, locations or plans can put individuals at risk of burglary, harassment or violence. Social networks and other platforms make it easy to broadcast such information widely, often without users fully realizing the consequences. When combined with other sources of data, seemingly harmless pieces of information can create detailed profiles of a person’s habits and vulnerabilities.

Another important dimension is fairness and non-discrimination. If organizations collect and analyze large amounts of personal data, they may make decisions that affect employment, insurance, credit, access to services, or opportunities in ways that systematically discriminate against certain groups. Attributes such as gender, age, ethnicity, religion or sexual orientation can be used explicitly or implicitly in decision-making systems. Protecting privacy, especially for sensitive attributes, is one way to reduce these risks.

Finally, privacy is intimately linked to autonomy. When individuals feel that they are constantly being observed, whether by governments or companies, their freedom to act and express themselves may be reduced. This “chilling effect” is particularly serious in societies where freedom of speech and political dissent are already fragile. By limiting pervasive surveillance and giving people control over their data, privacy protections help safeguard the range of actions and choices that individuals can reasonably make.

1.4. Historical and Legal Evolution of Privacy#

Modern notions of privacy as a legal right emerged in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. One famous early statement comes from the 1890 essay by Warren and Brandeis, which framed privacy as the right to be let alone. This arose at a time when photography and portable cameras allowed journalists and others to capture intimate images without the consent of the people involved. The concern was not only about property or physical harm, but about unwanted intrusion into personal life.

Warren II y Brandeis, 1890

Right to be left alone.

After the Second World War, privacy was recognized as a fundamental human right in international law. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted in 1948, states that no one should be subjected to arbitrary interference with their privacy, family, home or correspondence. Originally, this referred mainly to letters and telephone communications, but in contemporary interpretations it applies equally to email, messaging and other digital communications.

Article 12, Universal Declaration of Human Rights

No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.

In the European Union, the Charter of Fundamental Rights goes further by distinguishing between the right to private life and the right to protection of personal data. The latter explicitly requires that personal data be processed fairly, for specific purposes, on a legitimate basis (such as consent or legal obligation) and under the control of independent authorities. This evolution in legal thinking culminated in the GDPR, which is currently the central framework for data protection in Europe.

Article 7, Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, 2000

Everyone has the right to respect for his or her private and family life, home and communications.

Article 8, Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, 2000

Everyone has the right to the protection of personal data concerning him or her.

Such data must be processed fairly for specified purposes and on the basis of the consent of the person concerned or some other legitimate basis laid down by law. Everyone has the right of access to data which has been collected concerning him or her, and the right to have it rectified.

Compliance with these rules shall be subject to control by an independent authority.

1.5. What Counts as Personal Data?#

The GDPR defines personal data as any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person. In practice, such data can take many forms. It is useful to distinguish three broad categories: direct identifiers, indirect identifiers and sensitive data.

Direct identifiers

Attributes that uniquely identify a data subject, such as their name or social security number.

Indirect identifiers

Attributes that, when combined, can uniquely identify a data subject, such as age, gender, and address. Also known as quasi-identifiers.

Sensitive information

Attributes that reveal especially protected information about the data subject, such as a medical diagnosis, sexual orientation, or religious beliefs.

Direct identifiers are data items that uniquely identify a person on their own. Examples include full name, national identification number, social security number or phone number. Because they point directly to a specific individual, these fields are typically the first targets for protection measures such as removal, masking or encryption.

Indirect identifiers, also called quasi-identifiers, are data attributes that do not uniquely identify a person on their own but that can do so when combined with other information. Age, gender, address, occupation or IP address are typical examples. A single attribute might correspond to many people, but several attributes together may narrow down the possibilities to a single person. A classic illustration is that knowing someone’s date of birth, gender and postal code is often enough to re-identify them in many datasets. Another example discussed in class is a description like “American politician, former senator, member of the Democratic Party, President of the United States,” which leaves little doubt about whom we are referring to, even without stating a name.

Sensitive personal data are those data that reveal particularly intimate aspects of a person’s life, and that can lead to significant harm if misused or disclosed. Health information, diagnoses, laboratory results, mental health status, sexual orientation, political opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs, genetic information and biometric data all fall into this category. The GDPR treats many of these as “special categories of data,” placing strict limits on how they may be processed and stored.

Direct identifiers |

Indirect identifiers |

Confidential information |

|---|---|---|

Name |

Age |

Transactions (e.g. purchases) |

Email address |

Gender |

Salary |

Mobile phone number |

Race |

Credit ranking |

National ID number |

Date of birth |

Insurance policy |

Passport number |

Address |

Medical status |

Account number |

Postal code |

Vaccination status |

SSN number |

Job title |

Sexual orientation |

Social media name |

Company name |

Religious beliefs |

Marital status |

||

Height |

||

Weight |

||

IP address |

||

GPS location |

These categories are not separate islands. Sensitive data may be linked to individuals via direct or indirect identifiers. Protecting privacy is therefore not only about hiding names but about understanding how combinations of attributes can reconstruct identity or reveal sensitive traits.

Example

Barack Hussein Obama II (born in Hawaii on August 4th 1961) is an american lawyer and politician who served as the 44nd President of the United States, from January 20th 2009 until January 20th 2017. He is a member of the Democratic Party, and was the first African American to serve as President. Previously, he had been a Senator for the State of Illinois.

Example

Barack Hussein Obama II (born in Hawaii on August 4th 1961) is an american lawyer and politician who served as the 44nd President of the United States, from January 20th 2009 until January 20th 2017. He is a member of the Democratic Party, and was the first African American to serve as President. Previously, he had been a Senator for the State of Illinois.

Example

Barack Hussein Obama II (born in Hawaii on August 4th 1961) is an american lawyer and politician who served as the 44nd President of the United States, from January 20th 2009 until January 20th 2017. He is a member of the Democratic Party, and was the first African American to serve as President. Previously, he had been a Senator for the State of Illinois.

Example

Barack Hussein Obama II (born in Hawaii on August 4th 1961) is an american lawyer and politician who served as the 44nd President of the United States, from January 20th 2009 until January 20th 2017. He is a member of the Democratic Party, and was the first African American to serve as President. Previously, he had been a Senator for the State of Illinois.

1.6. Contemporary Threats to Privacy#

The growth of digital infrastructures, networked services and data-hungry business models has produced a wide range of threats to privacy. Some originate from the state, others from private companies, and others from malicious actors or simple negligence.

State surveillance includes measures such as mandatory identity systems, extensive CCTV networks and targeted or mass interception of communications. The revelations about the NSA’s PRISM program, for example, showed how large volumes of data passing through major online service providers could be collected and analyzed by intelligence agencies. Even in democratic societies, there is an ongoing debate about how far such practices can go without violating fundamental rights.

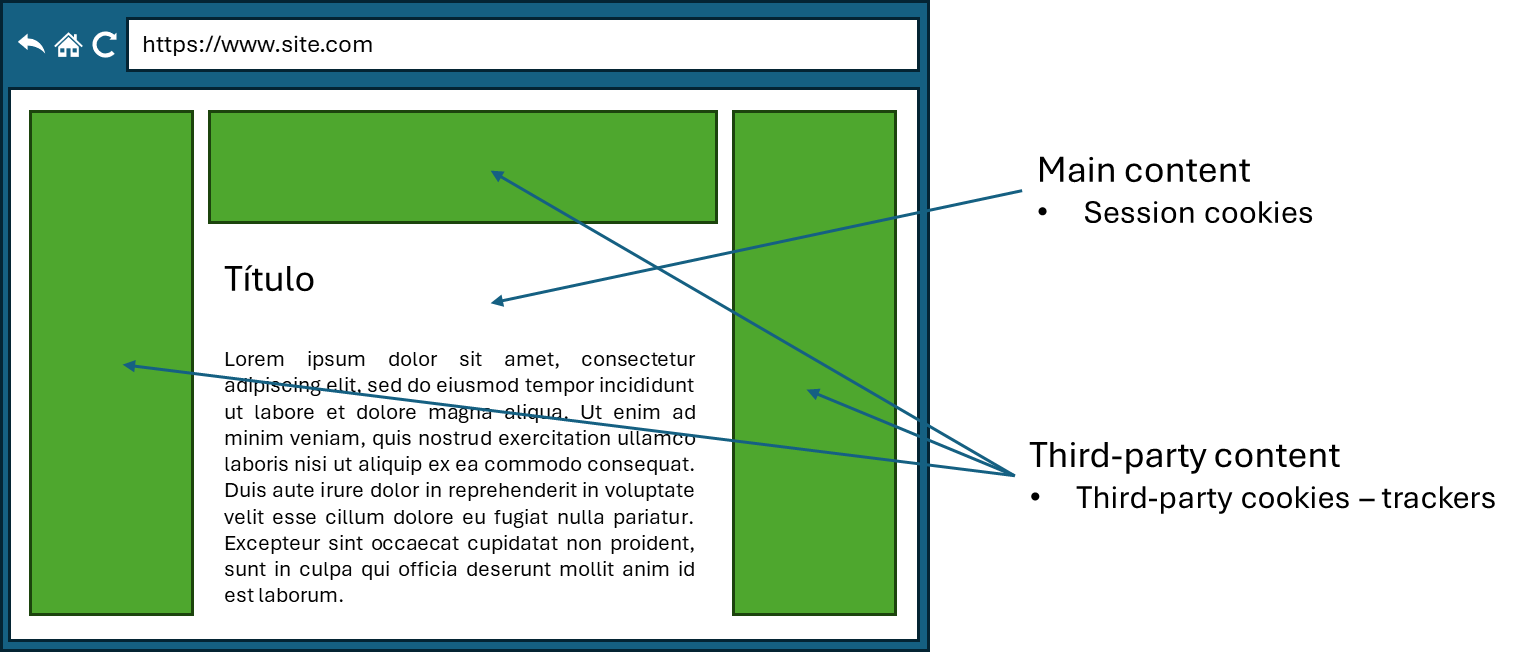

Corporate surveillance and profiling are driven largely by economic incentives. Many online services are financed through targeted advertising, which requires detailed user profiles. Websites often include third-party trackers based on cookies or fingerprinting (analyzing browser and device characteristics) that record visits, clicks and other behaviors across multiple sites. Social media platforms analyze interactions, likes and shares to infer interests and characteristics.

Example of third-party cookies in digital newspapers

Services like Am I Unique and EFF Cover your tracks can help users analyze their browser and system configuration to assess whether they are vulnerable to fingerprinting tactics.

Recommendation algorithms on platforms such as YouTube, TikTok or e-commerce sites use this data to keep users engaged or to sell more products. Although these systems may provide convenience or entertainment, they also accumulate large amounts of behavioral data that can be misused or repurposed.

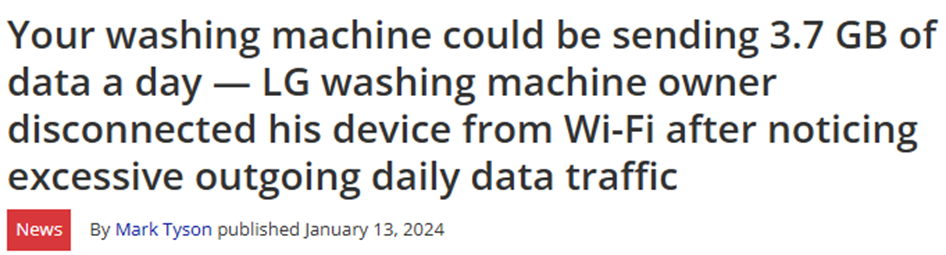

Smart devices and the Internet of Things extend data collection into physical spaces. Smartphones, wearables, home assistants, security cameras, robot vacuum cleaners and even household appliances gather and transmit data about locations, movements, daily routines and sometimes images or audio from inside private homes. In some reported cases, these devices have sent far more data than users might expect, raising questions about what is being collected and for what purpose.

Data brokers are organizations that specialize in gathering, aggregating and trading personal data. They may collect information from public sources, commercial transactions, social media, location histories and other datasets, then combine them into detailed profiles that are sold to advertisers, insurers or other clients. In the European Union, the GDPR places significant constraints on such activities, but in other jurisdictions this market is still largely unregulated.

Finally, data breaches represent an ever-present risk. When organizations store large volumes of personal data, vulnerabilities in their systems or human error can lead to unauthorized access. Once data has been leaked and copied, it is practically impossible to pull it back. Online services such as Have I Been Pwned reflect the scale of this problem by allowing users to check whether their email addresses and passwords have appeared in publicly known breaches.

1.7. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)#

The GDPR is the main legal framework governing personal data protection in the European Union. It applies not only to organizations established in the EU, but also to any organization worldwide that offers goods or services to people in the EU or monitors their behavior. As a result, many non-European companies align their practices with the GDPR in order to operate in the European market.

One of the aims of the GDPR is to harmonize data protection laws across EU member states, allowing personal data to flow freely within the EU while maintaining a high and uniform level of protection. The regulation also establishes conditions under which data may be transferred to countries outside the EU, namely when those countries provide an adequate level of protection or when specific safeguards are in place.

Over time, the GDPR has influenced legislation in other jurisdictions. Several countries and regions have adopted privacy laws that borrow concepts, structures and terminology from the GDPR, making it a de facto reference model for data protection worldwide.

1.7.1. Key Concepts and Roles in the GDPR#

The GDPR introduces a set of definitions that structure how we think about personal data and its processing. At the center is the data subject, the identifiable natural person whose personal data are being processed. Around the data subject are two main types of organizations: controllers and processors.

A controller is the entity that determines the purposes and means of processing personal data. It decides which data to collect, what to use them for, how long to keep them and to whom they may be disclosed. Because of this decision-making power, the controller bears primary responsibility for ensuring compliance with the GDPR.

A processor is an entity that processes personal data on behalf of a controller. A typical example would be a cloud service provider that stores or computes over personal data collected by a hospital, a university or a company. Even though the processor acts on instructions from the controller, it still has its own obligations under the GDPR and must implement appropriate technical and organizational measures to protect the data.

The regulation also defines processing very broadly. Any operation performed on personal data falls under this concept, including collection, recording, storage, organization, alteration, analysis, transmission, disclosure and even deletion. Consequently, almost any interaction with personal data is subject to the obligations and principles laid down by the GDPR.

Consent is another central notion in the GDPR. When consent is used as the legal basis for processing, it must be freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous. It should be presented in clear and plain language, and it should not be bundled unnecessarily with other terms or conditions. Importantly, consent must also be withdrawable: individuals must be able to revoke their consent at any time, and withdrawing it should be no more difficult than giving it in the first place. Although the regulation states this principle, it does not prescribe the exact technical mechanisms, which leads to significant variations in implementation.

The GDPR distinguishes between pseudonymization and anonymization as techniques for protecting data. Pseudonymization usually refers to replacing direct identifiers with artificial identifiers or codes while keeping the possibility of reversing the process under controlled conditions. This can reduce risk but does not remove the data from the scope of the GDPR. Anonymization, in contrast, aims at transforming the data in such a way that individuals are no longer identifiable, even when indirect identifiers are considered. Truly anonymized data are not subject to the GDPR, but achieving this in practice is difficult, especially with high-dimensional or rich datasets.

1.7.2. Principles for Lawful Data Processing#

Beyond definitions, the GDPR sets out fundamental principles that must guide all processing of personal data. These principles encapsulate the spirit of the regulation and provide a framework against which concrete practices can be evaluated.

Processing must be lawful, which means there must be a valid legal basis such as consent, performance of a contract, compliance with a legal obligation, protection of vital interests, performance of a task carried out in the public interest or legitimate interests pursued by the controller or a third party. What counts as legitimate interest is intentionally broad, but controllers must balance their interests against the rights and freedoms of data subjects.

Processing must be fair. This principle addresses the imbalance of power between individuals and organizations. Even if processing is technically legal, it may still be unfair if it exploits users’ lack of information, locks them into undesirable arrangements or treats them essentially as raw material rather than as rights-bearing individuals.

Transparency requires that data subjects be informed in clear and accessible terms about what is being done with their data, by whom and for what purposes. Privacy policies, cookie banners and other notices are practical manifestations of this principle, although in many cases they remain too complex or vague.

Purpose limitation states that personal data should only be collected for specific, explicit and legitimate purposes, and not further processed in ways that are incompatible with those purposes. This is meant to prevent organizations from hoarding data just in case and then reusing them for unrelated goals.

Data minimization complements purpose limitation by requiring that only the data necessary for the stated purposes be collected and processed. This is a direct counter to the tendency to gather as much data as possible simply because it might be useful later.

Accuracy requires organizations to keep personal data up to date and to correct inaccuracies without undue delay. Storage limitation requires them not to retain data in identifiable form for longer than is necessary for the purposes for which the data were collected.

Finally, integrity and confidentiality require that personal data be processed in a manner that ensures appropriate security, including protection against unauthorized or unlawful processing and against accidental loss, destruction or damage. Accountability ties all these principles together by holding controllers responsible for complying with them and for being able to demonstrate that compliance to supervisory authorities.

The GDPR also imposes special restrictions on certain categories of data, including health data, biometric data, genetic data, racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs and trade union membership. Processing of these special categories is generally prohibited unless specific conditions are met, such as explicit consent, important public interest, preventive or occupational medicine, public health or scientific research with appropriate safeguards. Genetic data, in particular, are highly sensitive because they reveal information not only about the individual data subject but also about family members and potentially descendants.

1.7.3. Rights of the Data Subject#

One of the most visible contributions of the GDPR is the set of rights it grants to data subjects. These rights are intended to give individuals more control over their personal data and to increase transparency and accountability.

The right of access allows individuals to obtain confirmation that their personal data are being processed, and to receive a copy of those data along with information about the purposes of processing, the categories of data, the recipients, storage periods and other relevant details. In principle, this should enable people to understand who holds information about them and what is being done with it.

The right to rectification allows individuals to correct inaccurate or incomplete personal data. For example, if someone’s address or health record contains errors, they should be able to have those errors fixed.

The right to erasure, often referred to as the right to be forgotten, gives individuals the ability to request deletion of their personal data under certain conditions, for instance when the data are no longer necessary for the original purpose, when consent is withdrawn and there is no other legal basis, or when the data were processed unlawfully.

The right to restrict processing allows individuals to request that their data be stored but not actively processed, for example while the accuracy of the data is being contested. The right to data portability allows individuals to receive their personal data in a structured, commonly used and machine-readable format, and to transmit those data to another controller. This is especially relevant for services where switching providers would otherwise be difficult because of data lock-in.

The effectiveness of these rights depends heavily on how organizations implement them. Some, such as Google, provide user-friendly dashboards and tools that make it easy to download, correct or delete data. Others require complex procedures or make the process obscure. Nonetheless, the legal framework establishes a clear baseline of what people can legitimately demand.

1.7.4. Obligations of Controllers and Processors#

To support these rights and principles, the GDPR imposes concrete obligations on controllers and processors. They must implement appropriate technical and organizational measures to ensure and to be able to demonstrate that processing is performed in accordance with the regulation. This includes keeping detailed records of processing activities, defining policies and procedures, training staff and regularly reviewing their practices.

For processing operations that are likely to result in a high risk to the rights and freedoms of individuals, controllers must carry out Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs). These assessments analyze the necessity and proportionality of processing operations, the risks they pose and the measures taken to address those risks. DPIAs are particularly relevant in contexts involving new technologies, large-scale processing of sensitive data or systematic monitoring of public areas.

The GDPR also introduces the concepts of privacy by design and privacy by default. Privacy by design means that data protection principles and safeguards should be incorporated into the design of systems, services and business processes from the outset, rather than bolted on as an afterthought. Privacy by default means that, by default, only the minimum amount of personal data necessary for each specific purpose should be processed, and that default settings should favor privacy rather than exposure.

Many organizations are required to appoint a Data Protection Officer (DPO). The DPO is an independent internal role responsible for informing and advising the controller or processor about their obligations, monitoring compliance, providing advice on DPIAs and acting as a contact point for supervisory authorities and data subjects.

When data breaches occur, controllers have an obligation to notify the relevant supervisory authority without undue delay, and in some cases to inform the affected data subjects as well, especially when the breach is likely to result in a high risk to their rights and freedoms. The extent to which a company cooperates and the seriousness of its preventive measures can influence the fines and other sanctions that may follow.

1.7.5. Practical Considerations#

Although the GDPR provides a detailed legal framework, many practical questions remain. For example, the regulation states that withdrawing consent should be as easy as giving it, but does not define exact standards. As a result, some services offer a simple one-click mechanism to revoke consent, while others require users to navigate several layers of menus or send formal letters. Enforcement in this area is still evolving.

When personal data have been breached and made public, the law can impose fines and require changes in behavior, but it cannot make the leaked information disappear. Individuals can withdraw consent for future processing, change passwords, monitor their accounts and so on, but the underlying fact remains that the data are in the wild. This reality underscores the importance of preventive measures and data minimization, as well as the need to think carefully before collecting or sharing sensitive information in the first place.